By Pamela Tom

It was 1987. Lee Magnuson learned that he had HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that would evolve into a global AIDS pandemic.

HIV/AIDS infection had swelled at an alarming rate since doctors first discovered HIV six years early—mostly in young gay men. Accompanying the snowballing shock and fear about HIV and AIDS, a new age of “safe sex” practices or condom use emerged.

But today, as Magnuson— who is gay—readily agrees, condom use is down in the gay community. PrEP, a daily pill that stands for “pre-exposure prophylaxis” to prevent HIV infection, may be making people feel sex is safe without protection.

A recent study of gay and bisexual men found that because of PrEP, the rate of condom use decreased 15 percent, from 46 to 31 percent between 2013 and 2017. Furthermore, heterosexual men and women of the millennial generation, including sexually active college students, are also abandoning safe sex practices as the alarming nature of the AIDS crisis fades into history. In reality, as of 2016, nearly 37 million people worldwide are living with HIV/AIDS, according to HIV.gov.

It doesn’t take a mathematician to calculate the impact of decreased condom use on the enormous number of people who are already or will be infected with HPV, the human papillomavirus. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection or STI in the U.S.

HPV can cause cervical, anal, and oropharyngeal cancer.

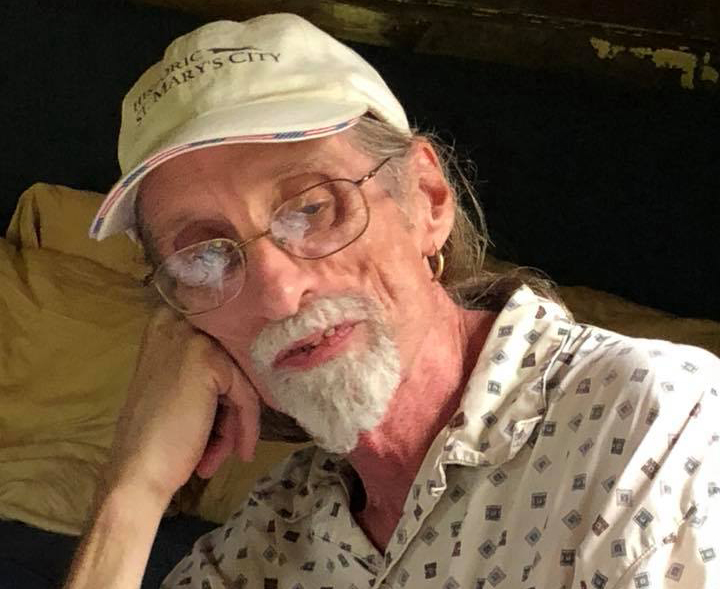

Lee Magnuson, HPV tonsil cancer survivor

Which brings us back to Lee Magnuson, now 64, who lives in Washington D.C. Decades of taking HIV-fighting drugs have taken their toll on his body. The medications caused his bones to become brittle and he broke three of his four limbs. He also blames the HIV drugs cocktail for high cholesterol and quadruple bypass heart surgery

After surviving HIV for decades, in February 2018, Magnuson was diagnosed with stage 2 HPV-related tonsil cancer. He had no pain but one day when he was brushing his teeth, he saw in the mirror that his right tonsil was much larger than the left one.

His doctor shrugged it off. Magnuson says in his experience, younger doctors are not conducting physical exams like his previous doctors did in the past.

“My old doctor would look in my throat on every visit. My new, younger doctor is in his 30’s and has a large gay practice but never touches me,” says Magnuson. “When I pointed out that I was having a hard time swallowing my large HIV pill, he told me there wasn’t much of a chance that it could be cancer because I’m not a smoker.”

Magnuson pursued an answer. He credits his head and neck surgeon, Dr. Matthew L. Pierce, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, with saving his life after ordering a biopsy of the tumor. As a self-professed gourmand, Magnuson opted to have surgery over radiation treatment which can cause decreased saliva and altered taste. Dr. Pierce removed the lymph nodes on the outer part of Magnuson’s neck, plus his right tonsil and part of his tongue.

“Talking and eating were difficult at first. I had a cleft palate feeling,” says Magnuson.

He relied on a feeding tube for the first few days after surgery and lost 14 pounds because he could barely eat for the first month. He had to learn how to chew and swallow carefully and regain his normal speech.

Throughout Magnuson’s HPV tonsil cancer battle, his partner, Keith, was there—taking him to doctor’s appointments, doing the shopping, and helping him. Magnuson undergoes regular PET scans but it is still too early to know if the surgery alone was successful.

But this proven survivor isn’t slowing down his pace. Living next door to the Washington Blade, a publication that covers the LGBT community, the retired Embassy of Sweden administrative worker is determined to encourage his peers to protect themselves against HPV.

“There is a great need for more awareness about HPV by doctors and the public, especially in the gay and HIV communities,” says Magnuson.

Magnuson is speaking out to educate people, including physicians, about the risk factors and how to prevent HPV infection with Gardasil 9, known as the HPV vaccine.

The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine to girls and boys at 11 or 12 years, but the vaccination series may begin at age nine. The recommendations include vaccination for females up to 26 years and males up to 21 years although males 22-26 may also be vaccinated. This fall, the FDA may decide whether to expand the recommended ages for HPV vaccine from 9 to 26 years-old to 9 to 45 years-old. Vaccine manufacturer Merck proposed the expanded age range to include more adults.

Magnuson hopes more young gay men will get vaccinated and he is helping to spread the word.

“I’ve always said there’s a difference between privacy and secrecy. Back in the 80’s, people wouldn’t even tell their doctors they were gay and so they wouldn’t get tested for HIV,” says Magnuson. “I was always open about my HIV status and I want people not to be afraid about HPV either. There are resources and HPV head and neck cancer doesn’t have to be a death sentence.”

But while supporting the HPV vaccine, Magnuson observes that there is a code of silence about sexual practices and HPV. He hopes his advocacy work will reduce the HPV stigma and encourage more people, especially young gays, to get vaccinated.

“Many young gay people today weren’t even born when my friends were dying of HIV. I wish they would take HPV more seriously,” says Magnuson.

Leave a Reply